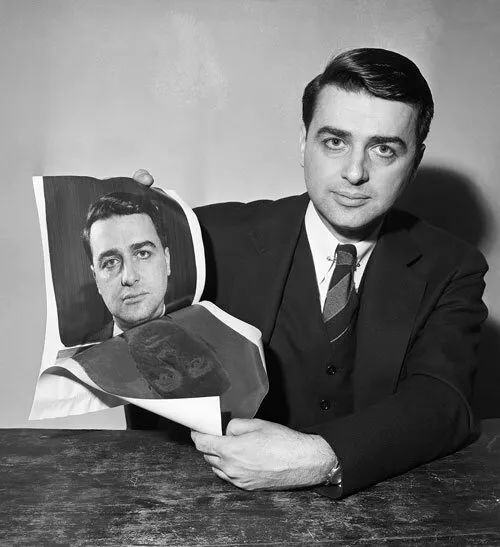

Edwin Land - Inventor of Instant Photography

Edwin H. Land (1909–1991) was the innovative inventor responsible for conceiving of and perfecting instant photography. Known simply as Polaroid, the system revolutionized traditional photography by compressing darkroom processes into an integrated film unit and producing a final photograph in the seconds following the click of a camera shutter.

As a boy, Land was fascinated by light. In particular, he was drawn to the natural phenomenon of light polarization.

Polarization refers to a physical property of light waves. As the waves move forward, they vibrate vertically, horizontally, and at all angles in between. A polarizer acts like a slatted screen, with long, thin, parallel openings. These invisible slats stop all angles of light except those parallel to the openings. By doing so, polarizers provide the ability to select light waves with particular orientations.

Natural polarizers (Quinine - the most effective antimalarial medicine then known - was produced from cinchona, a tropical plant grown primarily in Indonesia) were effective at reducing glare. But were expensive.

He worked to develop a synthetic polarizer. He worked to arrange a mass of microscopic synthetic crystals that would mimic the natural crystals. He created fine polarizing crystals, suspended them in liquid lacquer, and aligned them using an electromagnet. He then pulled a sheet of celluloid (a thin, clear plastic) through this solution to make a continuous sheet of crystals. As the lacquer dried, the crystals retained their orientation, and the result was a polarizing sheet that was thin, transparent, and pliable.

In 1929, Land applied for his first patent, a method for producing his polarizing sheets.

By 1930, Land had identified a more promising way to manufacture polarizing sheets: Instead of using electromagnets, he could apply the tiny crystals to a plastic sheet and, by stretching it, achieve parallel alignment of the crystals. Although it took several years to perfect, this method resulted in the commercial production of polarized sheets.

In 1932, Land and George W. Wheelwright, III (1903–2001), formed Land-Wheelwright Laboratories in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to manufacture polarizers. The company’s inexpensive polarizers were used in photographic filters, glare-free sunglasses, and stereoscopic products that gave the illusion of three-dimensional (3-D) images. 3-D movies were created by applying polarizers to projectors and viewing glasses. The company also invented a new product called a vectograph that combined two still images taken from slightly different positions and printed as oppositely-polarized images; using polarized glasses, viewers saw a 3-D image of the subject.

In 1937, Land-Wheelwright became a public company named Polaroid Corporation after the trade name for the firm’s polarizing films.

In 1942, Land hired Robert Burns Woodward (1917–1979) of Harvard University as a Polaroid consultant to find an alternative to the use of quinine in the production of polarizers (quinine-based crystals were used to manufacture polarizers at the time).

In 1943, during a vacation in Santa Fe, Land took a photo of his daughter, Jennifer, who was then three years old. The girl asked her father why she couldn’t see the photo right away—at the time, photographs had to be developed professionally, a process that often took several days. Land was immediately taken by the concept of instant photography and set off on a long walk to think through the idea.

The instant photography system Land imagined was a radical departure from traditional film processing. In conventional photography, a photographer took a series of photographs on a roll of film and returned it to a laboratory later for development. There, a technician would work inside a darkroom, a specialized laboratory that contained the materials—chemical baths to start and stop the development, washing and drying equipment, and other supplies—needed to develop film and produce photographic prints. The entire process took several minutes in the laboratory and usually several days from the time a photographer dropped off the film until a print was ready for retrieval.

Land’s system required a new kind of camera and film, a system that would compress all of the components of a conventional darkroom into a single film unit, to be processed in under a minute after being ejected from the camera. If successful, the system would allow users to evaluate and share images moments after they had been taken, a transformational change from traditional photography.

As in traditional photography, light entered the camera through a lens and was reflected onto a light-sensitive film that recorded a negative image of the scene. (In a negative, dark areas of the scene appear light and light areas appear dark.) After the silver halide crystals in the film were exposed to light, they were reduced to metallic silver. From this negative, a positive photograph could be developed.

The key to Land’s system was a film unit that contained both the negative film and a positive receiving sheet joined by a reservoir that held a small amount of chemical reagents (including sodium hydroxide, a strong base) that started and stopped film development. The reservoir, called a pod, was sealed within the film unit, making the entire process appear dry for the consumer even though it used liquid developers. When the film was released from the camera, a pair of rollers at the mouth of the camera bit the pod, rupturing it and allowing reagent to be forced evenly across the film, coating the entire image area. As the reagent spread, various chemicals worked to remove the unexposed silver halide from the negative, release it onto the positive layer at the top of the film unit, and reduce it, producing the final image.

From 1943 through 1946, the instant camera was kept secret at Polaroid’s laboratories as multiple challenges were resolved.

In fewer than five years, Polaroid had invented and mastered all of the necessary new technologies to demonstrate Land’s instant photography system. Land made the first public demonstration of instant photography on February 21, 1947, during a meeting of the Optical Society of America in New York City. Newspapers covering the event called the invention “revolutionary.” The following year was dominated by resolving challenges the company faced in bringing the system from the laboratory to commercial-scale manufacturing.

The first Polaroid camera, called the Model 95, and its associated film went on sale in 1948 at a department store in Boston. The cameras sold out in minutes. The Model 95 produced only sepia-toned images, and after the film emerged from the camera, photographers had to wait exactly 60 seconds before peeling off the negative backing of the image. Although it required precise operation by photographers and did not exceed the quality of traditional films, customers loved the system’s promise of nearly instant results.

A true (non-sepia) black and white version followed in 1950.

These films required the additional step of manually swabbing the developed image with a polymer coating to prevent darkening of the photograph.

The series of innovations released by Polaroid over the next decade reduced the early problems and improved picture quality remarkably.

By 1957, the New York Times called instant photography “equal in tonal range and brilliance to some of the finest prints made by the usual darkroom routine.”

Polaroid Corporation grew rapidly as instant photography exploded in popularity.

By the 1960s, traditional photography offered color films to the amateur photographer, and thus the next challenge for Polaroid was to develop instant color film.

More complex than either sepia or black and white photography, color photography used three separate negative layers to record colors. The infinite number of color nuances captured by the human eye can be reproduced by appropriate intensities of three colors—red, green, and blue. They are developed in a photograph using the complementary dyes cyan, magenta, and yellow. Starting in the late 1940s, Land and his team worked with traditional methods for producing color photographs, but they quickly learned to adapt to the thin confines and short time-frames required of Polaroid color photography.

Instead of using separate dye and developer molecules for each of the three colors used in film, project leader Howard Rogers (1915–1995) proposed, and then led the creation of, new compounds called dye developers in which both components were tethered together. These new molecules served both functions and simplified the overall film unit.

Polaroid’s color film debuted in 1963. Sales of Polaroid film, already rapidly increasing, expanded six-fold in the following decade. For Polaroid, color instant photography represented an enormous commercial and technical success.

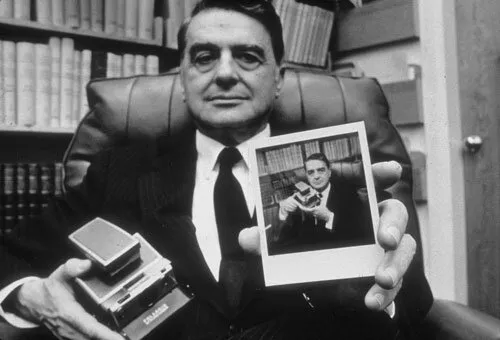

The crowning chapter of the Polaroid system was the development of the SX-70 camera and film. The project represented ultimate simplicity and reward for photographers—all they had to do was press the camera button and watch as the image developed before their eyes.

Until this point, Polaroid films required a step that interfered with Land’s vision of absolute one-step photography: After being ejected from the camera, the user had to peel back the negative sheet to reveal the final photograph. Some early films required additional steps by the user, such as swabbing the developed image with a coating to stabilize it or adhering the image to a hard backing to prevent curling.

The development of the SX-70 and its film required a complete reformulation of the Polaroid system. Above all, the film was integral, meaning that the negative, positive, and developers were all contained within a film unit and would remain there after developing.

The simplicity of the SX-70 system for photographers belied its technical complexity. Within the 2 millimeter thick film unit was a sandwich of thin polymer sheets, a positive image-receiving sheet, reagent, timing and light reflecting layers, and the tri-color negative—17 layers in total. The camera itself was a remarkably sleek design. When it was first sold in 1972, the product represented the culmination of Land’s 1943 dream of absolute instant photography.

He retired from Polaroid in 1982, 50 years after founding its predecessor company. Over the course of his career, Land earned 535 patents. He died on March 1, 1991, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Until this point, Polaroid films required a step that interfered with Land’s vision of absolute one-step photography: After being ejected from the camera, the user had to peel back the negative sheet to reveal the final photograph. Some early films required additional steps by the user, such as swabbing the developed image with a coating to stabilize it or adhering the image to a hard backing to prevent curling.

The development of the SX-70 and its film required a complete reformulation of the Polaroid system. Above all, the film was integral, meaning that the negative, positive, and developers were all contained within a film unit and would remain there after developing.

The simplicity of the SX-70 system for photographers belied its technical complexity. Within the 2 millimeter thick film unit was a sandwich of thin polymer sheets, a positive image-receiving sheet, reagent, timing and light reflecting layers, and the tri-color negative—17 layers in total. The camera itself was a remarkably sleek design. When it was first sold in 1972, the product represented the culmination of Land’s 1943 dream of absolute instant photography.

He retired from Polaroid in 1982, 50 years after founding its predecessor company. Over the course of his career, Land earned 535 patents. He died on March 1, 1991, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

American Chemical Society National Historic Chemical Landmarks. Edwin Land and Polaroid Photography.

http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/land-instant-photography.html

(accessed April 18, 2021).

What Brands Make Instant Film Cameras?

Let’s take a look at the brands out there:

·Fujifilm

·Leica

·Lomography

·Impossible Project

·Mint Camera

·Polaroid

Fujifilm manufactures their own brand of Instant film called Instax. It’s available in Square, Mini and Wide (at the moment). But they also make their own cameras.

Leica makes their own Instax camera as well. It uses the same film Fujifilm produces.

Lomography: same thing. In fact, they’ve got a whole lineup of various instant film camera offerings on the market.

The Impossible Project is the child of a company that bought all of Polaroid’s machinery to figure out how to make the film when Polaroid shut down their factories years ago. So they make a whole lot of different formats for many vintage Polaroid cameras and even those that can be used in the newer cameras that have come out recently. Impossible Project film is different from Fujifilm’s and it won’t work in their cameras. In a way, they’re the true successor to Polaroid.

Mint Camera makes fantastic cameras that take both Impossible Project’s film and Fujifilm’s films.

But Fujifilm and Impossible Project use actual film. You can cut an Impossible Project image open and find the negative. Yup, that also means that there is a full chemical process that happens while making the image. Each film print is sort of like a darkroom experience in every shot.

Then there is the Impossible Project: the makers of film for old Polaroid cameras and new cameras that have been made in the past few years. They make Spectra film, 600 series film, SX-70, 8×10 film, and what they’re calling I-1 film which is essentially the 600 series film but without a battery built into the film cassette.

Polaroid doesn’t make instant film anymore. Instead, they make a digital camera that prints out small little prints on a paper called zInk. It’s got the dye in it already.

Polaroid indeed does not do instant film. Polaroid, again, isn’t making film. But instead what they make are these little zInk packets. They’re paper and the camera has a printer built into it.

Polaroid zInk works by basically just being paper that is printed upon. That’s it.

Instax and Impossible Project film, however, are actual film development. When you shoot an image there is a chemical process and a little darkroom inside each pack. With Instax film, the emulsion is more stable and accurate. With Impossible, the emulsion is a bit less stable and the image needs to be shielded from daylight for a while to ensure the best processing. So basically putting it in your pocket helps a lot. With that said, Instant film also needs a warm environment to work best in. Instant film from both Fujifilm and Impossible work best in temperatures above 55 degrees Fahrenheit.

How to Get Better Image Quality

This is the really tricky question to have answered: image quality. Most instant film cameras have plastic lenses. The only way to get better quality is to go after the cameras with glass lenses.

Lomography, Impossible Project and Mint camera are the only brands who have cameras that can do this.

Storage of Instant Film Prints and Instant Film

If you’re using Fujifilm Instax film, then you can store your prints however you’d like. They don’t really fade and the quality stays the same.

Impossible film needs to be shielded from daylight because otherwise you’ll get fades. In the case of their black and white film, you’ll get the images turning sepia after about a year.